Reviewed By Sarah Sliman

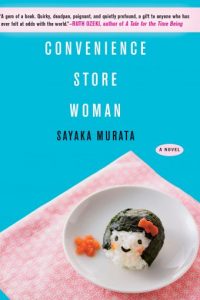

Translated into English in July 2018 by Ginny Tapley Takemori, Sayaka Murata’s English debut Convenience Store Woman puts a unique twist to a familiar story of those who feel trapped by society, forced to hide their true selves and conform to the norms around them, swapping oddities and quirks for forced smiles and complacent nods. Over a brief 163 pages set in Tokyo, thirty-six-year-old single Keiko Furukura lives out her days mimicking those around her, performing her daily tasks as a convenience store worker while struggling to grasp the worry her family and friends have over her complete absence of social and sympathetic understanding.

Keiko’s world is one of dark surrealism, crafted so believably that her warped perception of society seems strongly grounded in reality. After incidences of violence in her youth, innocently brought on by a desire to help and follow directions in the logically most efficient way, Keiko withdrawals and soon learns that those not welcomed by society must keep quiet and adapt the natures of those around them to survive. She does so, blending in and learning to copy and paste the facades her peers put on in order to blend in, and eventually succeeds, going to a university, but mostly spends time alone. In order to make some money during college, she applies to work in the newly opened “Smile Mart” and finds purpose and meaning in greeting customers with a cheery “Irasshaimasé!” and restocking shelves, perfecting her role as a “normal” person. However, with increasing pressures from her family and friends to find a husband and a real career after over eighteen years of working at the Smile Mart, Keiko’s world of rice balls and ice pops begins to crumble and melt around her.

As Keiko struggles to explain why she is the way she is, Murata seamlessly blends flashbacks and present day narrative, letting Keiko’s quirky voice lead us through different stages in her life. Surprisingly, many can relate to her desire to fit in; most probably haven’t impulsively attempted to bludgeon a classmate in order to stop a schoolyard fight, but many can sympathize with her annoyance over her sister’s and mother’s nags about career and marriage. Her family’s persistence in “curing” Keiko hits close to home for those whose family’s would rather change them than have them as they are.

Keiko’s disinterest in sex, love, and marriage are refreshing; the reader cannot help but to root Keiko on in her singleness, desperately pleading for her to rid herself of any parasitic partners or overtly intrusive friends in her life. Keiko, while not necessarily a hero, is a definite protagonist, uniquely having readers cheer on stagnant mediocrity over excellence in hopes that Keiko can find happiness in routine and order within the convenience store. However, Shiraha, a bitter freeloader with a grudge against society, throws a wrench in Keiko’s plans of feigned normalcy. His biting remarks sting; however, Keiko remains a stronghold for readers to grasp onto, guiding them through the tangled web of deceit and shame clouding Shiraha’s vision.

Murata’s highly praised Japanese prose carries over to English well; frank statements of sociopathic thoughts and tendencies lead to dark comedy, all while shining a light on criticisms of Japan’s society, which—can be seen in American society as well. Keiko’s dialogue comes off rather terse, but this serves well as she uses an awkward blend of dialects from those around her in order to mask her social incompetence; Shiraha’s rude and profane nature is also carried across easily, his mockery and objection to the “survival of the fittest” nature of society not at all unfamiliar to Western readers. However, others’ dialogue seems a bit more natural, but not enough. While most likely caused by colloquialisms not translating well from Japanese, some verbiage seems rather stiff and cookie cutter, coming off too forced.

The ending, while rather abstract and abrupt, is open enough to let readers imagine Keiko’s fate for themselves, a fitting end to such a quirky quick read. Murata’s style of writing reflects Keiko’s personal narrative—direct and clean cut with no flowery additives; it is so convincing that readers may find themselves balking at the audacity of her coworkers to gossip rather than tidying up shelves and preparing mango buns, slowly immersing themselves in Keiko’s way of thinking. In both Keiko’s fast paced Tokyo life and in readers’ society, it serves to provide a poignant message in an absurd and sinisterly comical manner, yet is so short that it both leaves the reader no excuse not to finish the novel and leaves with just enough of a palate for Murata’s prose that readers will be desperate for more.