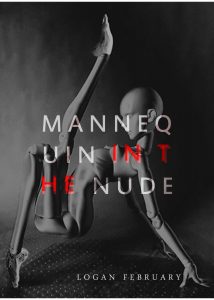

Reviewed by Tessa Fahey

“Nude” holds so many connotations for being our default setting. We see it as a state of vulnerability, but it can also hold shame or pride. In the Bible, Adam and Eve only develop shame about their nakedness after eating Forbidden Fruit from the Tree of Knowledge. So what is right? To be ashamed or to be ignorant? In his latest book of poetry, Mannequin in the Nude, Logan February fights to find a third option. The book is a celebration of self-love in a world of turmoil—a world full of mental illness, intolerance, and religious conflict. And yet, February is honest about his flaws and mistakes, completely open and completely unashamed.

The book is laid out in three acts, titled “witch dressed in red,” “witch dressed in black,” and “witch dressed in white” respectively. The titles are drawn from the Iyami Aje of Yoruba culture of Nigeria where February is from, or to be more accurate, the modern version of the Iyami Aje born out of a combination of Yoruba mythology and patriarchal European values. “In Yorùbá, àjé pupa, the red witch, holds a knife in each hand, the only one with the power to kill. … Almost as malevolent as her is the black witch, àjé dúdú. She curses and haunts and follows. … Later, I found the white witch. Àjé funfun. Protector, bearer of peace.” The titles seem to walk us through February’s mental state as he seeks peace of mind and becomes less tethered to grief and despair. However, the titles don’t wholly determine the subjects of each section as February never strays far from death, a naked, honest truth: the death of his father, his own suicidal tendencies, or the death threats used against him for his sexuality: “I sing for Death to come close / but not too close I’m only looking for / someone to kiss & go see Black Panther / with”.

While most of the poems are free verse, the book explores a variety of structures, including prose poetry. It’s an experimental journey through his experiences while seeking how best to interpret them. February deliberately controls the pacing and reading of each piece, using extra spacing, slashes, and columns to create unexpected pauses and new readings. The diversity in form and approach demonstrate profound skill as February finds new ways to ensnare the reader in a spiritual journey. And although he questions every religion and superstition he’s been caught in for the way they’ve rejected him (including the denomination of Christianity brought to Nigeria by colonizers), the poetry is reverent and meditative in a wholly spiritual way, on every subject ranging from God to pornography.

The most prominent series of poems is the one where February interprets those in his life through a mannequin: “Portrait of the Mannequin as…”. Poems range from portraits of his doctor and father in the first act, lover and mother in the second, and God and himself in the third, moving closer to himself and yet more divine. Each of these poems wield empathy to accept the experiences and resulting beliefs of everyone in his life, even those who may not offer him the same courtesy. Though many of the poems profess a deep loneliness or isolation, this series represents genuine care as he takes the time to understand all perspectives on himself. And yet that focus on himself is also indicative of self-awareness and self-care that permeate the whole book. Another series explores the seven deadly sins as they affect his life, and every poem offers an unexpected interpretation of the sin in an unashamed tone. It’s aware and defiant, naked and proud.

Mannequin in the Nude is a stunning look at a man finding peace and self-acceptance despite tragedy and suffering, and February has demonstrated mastery in his ability to take an audience’s breath away with just a few lines. And yet, it’s his technique in formatting and structure that truly stands out as the star of this book. The text reads like a diary exposing the darkest parts of himself and still it is an exploration of control over the audience and their readings of his poetry. He knows how you’ll read each poem because it’s a reading he molded. The book is despair and power all in one: “I am Yorùbá & death / in Yorùbá / is also a god.”