Reviewed By Rhonnie Bonner

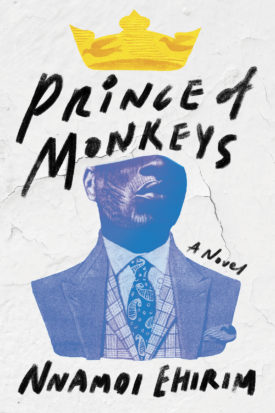

Empowerment from wealth or bonds: which is more important? How does one navigate and understand their place within a post-colonial and capitalistic society that is constantly challenging or incorporating Western culture into itself? How can you maintain your friendships and relationships within a society that is constantly dealing with political upheaval? What is self-actualization if external societal forces are always influencing you? And can you actually escape imprisonment? Nnamdi Ehirim wrestles with these questions in his debut novel Prince of Monkeys in 272 pages. Set in Nigeria, Prince of Monkeys is a kaleidoscopic and bildungsroman tale that follows Ihechi, a middle-class Nigerian, during the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Each society has its ways of thinking, values, beliefs, and mindsets that are shaped by the environment and cultural landscape; thus, Ehirim’s exploration of the human experience shows that Ihechi is also shaped by the society he inhabits. Therefore, Ihechi’s quest for self-actualization is complicated within the novel because people often become characters that are just acting out their roles as theorizing political activists, scheming capitalists, lovable prostitutes, sweet love interests, complicit bystanders, hypocritical reformists, passionate spiritualists, malicious madames, survival criminals or government-funded puppet politicians. Everyone has their role to play to function within this ecosystem.

As Ihechi struggles to claim his own identity for himself, he is greeted with other characters that have constructed a persona that works for them. Madame Messalina is not above taking revenge against anyone who gets in her way. Zeenat is the type of woman, any man would fight over and constantly think about even after she leaves. Tessy is a manipulative woman that disposes men once they have fulfilled their usefulness. Mendaus is a man that knows what he wants and won’t allow the love of money to corrupt him like the other shady political or powerful leaders. In a ghost of Christmas past fashion, a reappearing amoral character named Maradona drifts in and out of Ihechi’s life with a new identity. In comparison to the characters around him, Ihechi is constantly concerned with others’ opinions and morality. Despite corruption being used to secure safety and success within the novel, he hopes to achieve his goal and live ethically, which makes readers fear that more ambitious characters will take advantage of Ihechi’s almost passive disposition. Ehirim’s presentation of the characters make readers grapple with inquiries about self-actualization, ethics, and the bewildering human need to craft an identity in a world that does not allow us to make our own independent decisions.

Ihechi’s world is constantly changing due to the political upheaval in Lagos, Nigeria, which leads to an unfortunate series of events that impact Ihechi’s relationships with his family, friends, and shady acquaintances because of Ihechi’s almost indecisive nature. Ihechi lives his life meandering about in the novel, constantly allowing life to happen to him much to the dismay of the characters closest to him. Ihechi’s companions are often flummoxed by his devil may care attitude, especially since life is never monotonous in Lagos, Nigeria. The strength of the novel comes from the other characters’ actions and Ihechi’s reactionary actions that gives readers the blurring impression that Ihechi’s life is not much different from the oppressed and poor Nigerians, who lack self-determination.

Additionally, Ehirim’s concern with politics, spirituality, religion, gender, sexuality, class, tribalism, and identity in the novel shows that one cannot live within a post-colonial society without risking something, whether these risks involve the loss of freedom, body parts, damaged relationships, and loved ones. However, throughout the danger, loss, and tragedy experienced by the characters in Prince of Monkeys, Ehririm reminds readers that you have to continue to live in spite of everything for yourself even if it means you have to risk experiencing a social, mental, or physical death.

While the anticlimactic conclusion may leave readers wanting more of Ehirim’s writing and wondering what happens next for Ihechi, Prince of Monkeys is a work that leaves readers on edge by making them question whether the morally right choices are always the correct choices to make depending on one’s peculiar predicament due to an individual’s subjectivity. Reading Prince of Monkeys may remind you of other works, such as Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony and Tsitsi Dangarembga’s Nervous Conditions, that grapple with living in a society where you should harmoniously co-exist and feel satisfied with social conformity but the overarching issue of colonization that continues to impact the lives of people in your community. Therefore, if you enjoy episodic, postmodernist, and realism novels that deal with the post-colonial subjects’ articulation of their subject positions and how they navigate two seemingly separate worlds within a single society, you should add Nnamdi Ehirim’s Prince of Monkeys onto your list of books to read.