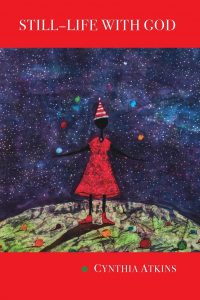

Reviewed By Riley Hines

The poetry within Cynthia Atkins’ Still-Life with God addresses an array of critical issues that many people—especially women—face during their lifetimes. With descriptive allusions, this collection of poems draws the line between hope and disappointment, while also highlighting the collective human struggle in achieving an authentic self unconstrained by barriers, social constructs, and most importantly, male violence. The “God” of this work takes on several forms, such as a medicine cabinet and a library, and represents not divinity, but an authority that we all have been taught to respect throughout our lives. This authority, or “God,” effectively silences the authentic self and forces people to become a shadow themselves in the wake of other’s thoughts and opinions. In this way, Atkins artfully shows how people become a “still-life” and are devoid from their own voices. As we’re told in “Hello Stranger,”

“It’s me – This voice inside a tin box

inside the intention to be a voice

of one, but we’re all crammed

in traffic – This grid is the lunatic

abyss inside a pickle jar.”

This entrapment and voiceless quality are echoed again in “Domestic Terrorism”,

“Terror is your voice going mute over every sidewalk and city block.”

and in “Letter To The Woman Who Had To Hang Up Her Coat”,

“A voice that no one else

Can hear is large and gangly

As a bomb in your throat.”

Divided into four parts, Still-Life with God invokes a certain train of thought, one that examines a struggle that has been prominent in the past, as well as the present. Each part functions as a cog in a larger work, each fitting together to allow the audience a clear view of the message being told. That being said, each section also works apart from one another. In this way, readers can go through the collection as it is presented, or they can pick and choose which poems to read while still arriving at a meaningful destination. Not only does the collection call attention to important issues such as male violence and eating disorders, but it also realizes the importance of language and the role it plays in people’s lives. Originally, the speaker comes to terms with the seemingly negative nature of language. As said in “Before the Lies”,

“I’ve learned that words matter, but words lie,”

and,

“Salutations rolling over

The teacher’s tongue – were talismans

Beyond the cracks, lies and laundromats.

The earth opened to a place where language

Hoards the silence, animals in a barn of breathing.”

Despite these outlooks on language, the reader can expect a kind of enlightenment, one that isn’t revealed until the end of the collection. The speaker finds a resolution where they are freed from “God.” In “Goddess in Purple Rain” and “God is a Myth,” song represents a release from the suffering self and reveals a trajectory towards the authentic self. Though the songs maintain the pain felt throughout the entirety of the collection, Atkins concludes with a hopeful perspective. In “God is a Myth,” Atkins writes,

“My past until this moment

is penciled in the way an artist suggests a cloud.

This is the narrative – repeat it, repeat it after me.

I never existed before this moment.

Under a stairwell, I could feel my fear

like skin caught in a zipper. The last touch

of red on the artist’s brush. I heard many cries,

like scrawny cats in the alley of my heart.”

Moments like this compel readers, luring them into a hopeful future while reminding them to keep a watchful eye on the events and lessons of the past.

Cynthia Atkins’ Still-Life with God is extremely relevant. She skillfully sets the tone in part one of her collection, setting an idyllic, old-fashioned scene with crackerjacks and Greyhound buses. In departing from part one, Atkins progresses into a more recent time, which underscores the idea that these struggles have existed and been faced by numerous people for a countless amount of years. Through the hypocrisy and negativity, Atkins unveils the universal human nature in which we set out to find something holy in material objects that are ultimately unholy. Her lyricism enraptures readers and shows us that we may not find what we’re looking for, but will gain something from the experience all the same. With this bold collection, she doesn’t shy away from important ideas and issues, and effectively outlines the many aspects of how people become something apart from themselves, while both losing and gaining something during the experience. Overall, her collection is thought-provoking and profound, imploring the reader to not only examine themselves, but also humans as a collective whole.